Read the full version of this article for free in my Substack

Exercise-associated muscle cramps are painful and spasmodic involuntary contractions of skeletal muscle during or immediately after a workout in otherwise healthy individuals. This topic is controversial, with conflicting evidence both supporting and refuting the widely held notion that dehydration and electrolyte imbalances are responsible for exercise-associated muscle cramps. Some people are predisposed to cramping during exercise, and the cause is multifactorial. In this article, I will discuss the potential causes of exercise-associated muscle cramps, their prevention, and the one solution that works once they occur.

🥹Importance of Understanding Muscle Cramps

Exercise-associated muscle cramps are a very common problem among athletes and are characterized by a sudden, painful, involuntary contraction of skeletal muscle that typically occurs during or immediately after practice. Understanding the causes and solutions can help athletes manage and prevent these cramps effectively.

Study Reference: Miller KC, McDermott BP, Yeargin SW, Fiol A, Schwellnus MP. An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps. J Athl Train. 2022 Jan 1;57(1):5-15. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0696.20. PMID: 34185846; PMCID: PMC8775277.

💧Dehydration and Electrolyte Imbalance Theory

The oldest and most widely recognized theory proposes that exercise-associated muscle cramps happen as a result of sweat-induced fluid and electrolyte (primarily chloride) losses. However, this theory was based primarily on clinical observations and anecdotal evidence.

Key Points:

- Dehydration and electrolyte losses are systemic phenomena – meaning that they affect the whole body equally. If this theory was completely accurate, then cramps would occur in random muscles, not on the working muscles exclusively.

- Several authors have demonstrated no differences in plasma volume, red cell volume, body mass lost, or plasma electrolyte concentrations during competition between athletes with and without cramps. (Schwellnus MP et. al. 2004), (R J Maughan, 1986),and (Schwellnus MP et. al. 2011)

- When measured, sodium and chloride losses along with sweat rate were only predictive of cramp-prone athletes in one out of 10 other sports studied. (Miller, KC et. al. 2020)

For a more complete list of expert opinion and both observational and experimental studies that refute this theory you can read this paper: Miller KC, McDermott BP, Yeargin SW, Fiol A, Schwellnus MP. An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps. J Athl Train. 2022 Jan 1;57(1):5-15. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0696.20. PMID: 34185846; PMCID: PMC8775277.

🧠💪🏼Altered Neuromuscular Control Theory

This theory proposes that cramps happen when fatigue and other risk factors contribute to a common pathway that produces an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory stimuli at the neuromuscular junction. This theory explains why cramps occur in exercising or actively contracting muscles exclusively.

Key Points:

- Cramps can be induced in the absence of dehydration or electrolyte losses (Miller KC, 2017).

- Poor conditioning, and higher exercise intensities are more consistently correlated with alterations at the neuromuscular junction than dehydration and electrolyte losses

- Spinal cord pathways in non-crampers consistently produce greater amounts of inhibitory stimuli than crampers (Khan SI et. al. 2007).

Although this theory better explains clinical and laboratory observations of cramping, it is not without limitations and inconsistencies. For example, there is some contradicting data in individual studies (Shang G, et. al. 2011), (Schwellnus MP et. al. 2011), and (Miller KC et. al. 2009), and it is still unclear how fatigue itself causes cramps mechanistically.

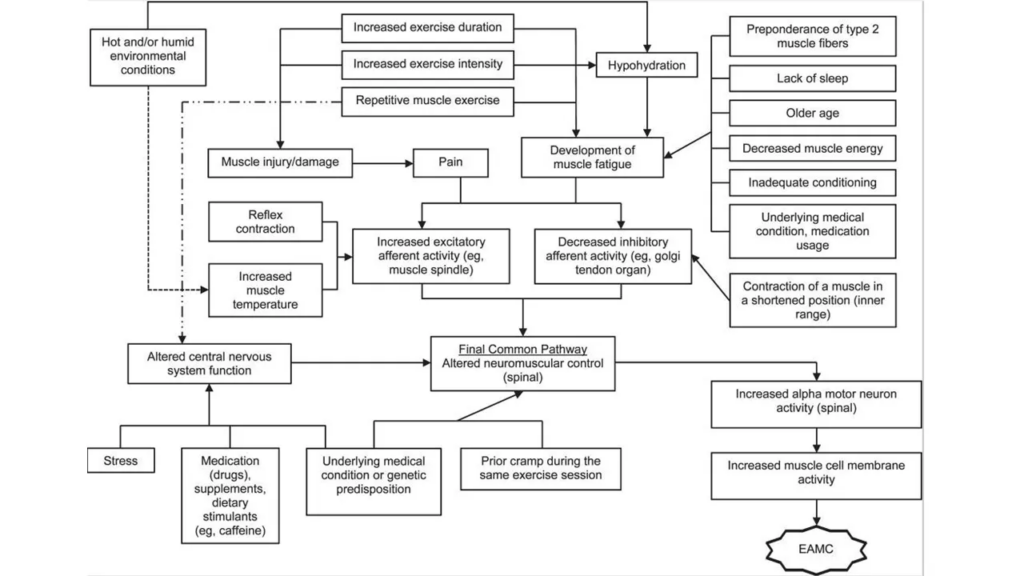

☝🏽🤓Multifactorial Theory

This model proposes that multiple factors interact to trigger a chain reaction that alters neuromuscular control and induces cramps. Importantly, this model suggests that a threshold must be reached before cramps occur, which can be positively or negatively affected by various risk factors.

Key Points:

- A threshold must be reached before cramps occur.

- Intrinsic and extrinsic factors interact to determine whether this threshold is surpassed.

- This theory explains why cramps occur in some individuals and situations but not others.

Diagram Reference: Multifactorial theory for pathogenesis of exercise-associated muscle cramps (EAMCs). Reprinted by permission from Miller KC. Exercise-associated muscle cramps. In: Adams WM, Jardine JF, eds. Exertional Heat Illness: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide. Springer; 2020:117–136.

💊Prevention

Many prevention and treatment recommendations exist, though most are based on anecdotal evidence. Here is a summary of prevention strategies available in the literature:

Prevention Strategies:

- Incorporate neuromuscular reeducation, plyometrics, or strength training into your training regimen.

- Include suitable rest periods after training to allow recovery and minimize the residual effects of muscle damage.

- Hydrate properly.

- Consume a nutritious, well-balanced diet that accounts for your unique carbohydrate, electrolyte, and fluid needs.

👨🏽⚕️Treatment

Nothing works in the acute setting other than static stretching of the affected muscle. Static stretching can be started immediately after the cramp occurs and can be performed actively (by contracting the opposite group of muscles) or passively (with help from someone else or yourself while trying to relax the affected muscle).

Additional Tips:

- ⚠️Food containing acetic acid (e.g., vinegar) or transient receptor potential activators (e.g., capsaicin) may help relieve cramps. These should be used infrequently and in small volumes (<100 mL). Only attempt in individuals without related food allergies.

🍌Do Bananas Help Cramps?

Contrary to popular belief, potassium is generally not considered an electrolyte of interest in the pathophysiology of cramps. Bananas, despite being rich in potassium, have not been shown to effectively prevent or treat muscle cramps.

Study Reference: Miller KC, et. al., 2012

While bananas may not offer an immediate curative effect on cramps, they still offer significant nutritional value and are an important component of my own post-training routine. So don’t stop eating them if you do.

Lastly, severe and frequent exercise-associated muscle cramps may be a sign of underlying conditions and require a medical evaluation. This article is not intended to be a replacement for that. Don’t be stubborn and go see your doctor.

FAQ

What are exercise-associated muscle cramps?

Exercise-associated muscle cramps are painful, involuntary contractions of skeletal muscle that typically occur during or immediately after exercise.

Do dehydration and electrolyte imbalances cause muscle cramps?

While dehydration and electrolyte imbalances are commonly believed to cause muscle cramps, evidence suggests that these are not the sole causes. Cramps can occur without dehydration or electrolyte losses.

How can I prevent muscle cramps?

To prevent muscle cramps, incorporate neuromuscular reeducation, plyometrics, or strength training into your routine, hydrate properly, and maintain a balanced diet.

What should I do if I get a muscle cramp during exercise?

The most effective treatment for acute muscle cramps is static stretching of the affected muscle. This can be done actively or passively.

Are bananas effective for preventing muscle cramps?

Despite popular belief, bananas are not effective for preventing muscle cramps due to their potassium content. However, they do offer significant nutritional value and can be part of a balanced diet.

Summary

Exercise-associated muscle cramps are a common issue among athletes, caused by multifactorial factors. Understanding the potential causes and effective prevention and treatment strategies can help manage and reduce the occurrence of cramps. Incorporate proper training, hydration, and diet to keep cramps at bay, and use static stretching for immediate relief.

Disclaimer: This content is provided for educational purposes only and should not be construed as medical advice. Always consult with your primary care physician (PCP) or a qualified healthcare professional before making any changes to your lifestyle, diet, or exercise routine. The information presented in this article is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. Individual results may vary. The author and publisher of this article are not responsible for any adverse effects or consequences resulting from the use or application of the information provided. Please use your own discretion and judgment when implementing any suggestions or recommendations.